Evangelism 101: "King's X" for Grownups

I suppose I'm dating myself here, but I recall as a child in the '50's hearing the term "King's X" called out during games involving "pursuers" and "fleers." In calling upon the authority of the King's signature, or X, the player thus demanded immediate immunity from being "tagged" or "captured." When honored (as it nearly always was) King's X thus secured a suspension of the normal rules of the game—much as crossing one's fingers behind the back granted permission to lie.

As a younger Christian I sometimes wondered why God didn't simply cry "King's X" regarding the sins of those who expressed contrition, thus sparing His Son that awful death on the cross. Why did Jesus have to die? Why could God not just "forgive" those sins? After all, if God is omnipotent, could He not simply place all the sins of those who expressed repentance under a cosmic "King's X" and declare them righteous?

Having spiritually grownup through Bible study I can now answer my own naive question: from God's perspective, forgiveness is not ignoring sin—it is separating the sin from the sinner. Even God cannot violate His own righteous edicts. In righteousness He had declared that "the wages of sin is death," and that "the soul which sins, it must die." Having declared these things He cannot "un-declare" them. In the rules of eternity there is no King's X.

Yet from 2 Pet 3:9 we know what God desires for all mankind. We read there that God is "not willing that any should perish..." In other words he would save us all. But the same Bible states with equal clarity that "all have sinned and come short of the glory of God," which means we must all die the second death—which is eternal separation from God.

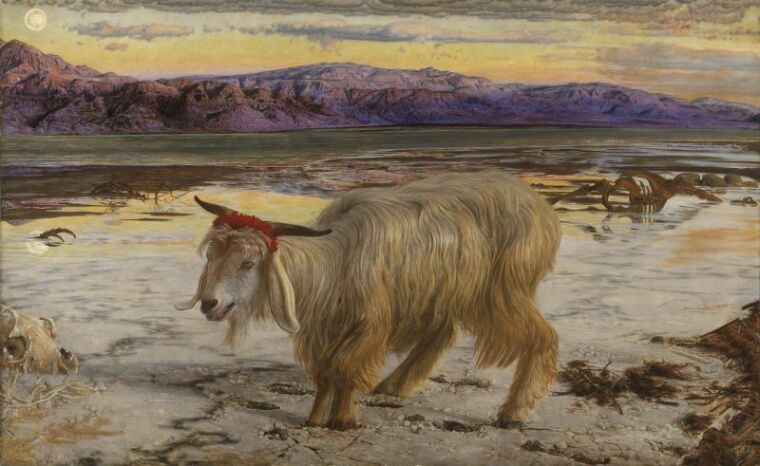

If God cannot simply overlook sin, does this mean He is rendered helpless by His own edict to spare mankind from the eternal consequences of their sins? Must they pay for their own—because there is no cosmic King's X? The answer is, "No," because of a rule which exists in the eternal realm and which God introduced into the earth many centuries ago. It is the "rule of the Scapegoat."

Leviticus chapter sixteen details how the ancient Israelites were to observe their annual Day of Atonement. The high priest (Aaron)—after prescribed ritual cleansing for himself—was to enter into the Holy of Holies on Yom Kippur and sprinkle the mercy seat with the blood of a bull and a goat. In this ritual a third animal also played a significant role. Not only was Aaron to select the bull and the goat to be sacrificed but a second goat which was to be sent off into the wilderness. (Aaron did not decide which of the two goats was which. He was to cast lots to make the determination, thus allowing the decision to be God's alone.)

Before he sent the second goat off into the wilderness, Aaron was to place his hands on its head while confessing out loud the sins of the nation. Through this God-ordained ritual those confessed sins were—in the mind of God—transferred from His people to the innocent animal. That goat became the Scapegoat. When it was then led off into the wilderness, it carried the sins of the people on its head. God thus separated the sins of Israel from the sinners to whom they belonged. In other words, He forgave them.

Why is this important to Christians today? Because as both the Old and New Testaments declare, Jesus was our Scapegoat. On the cross He became the antitype to which the Yom Kippur Scapegoat was the pre-figuring type. The Old Testament puts it this way: "All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned—every one—to his own way; and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all" (Isa 53:6). In the New Testament we read, "He has made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him" (2 Co 5:21).

Jesus fulfilled many Old Testament types, but on the cross His fulfillment of the role of Scapegoat—that of separating sins from sinners whom God would save—was paramount.

This is why Jesus had to die. Far from any thought of placating an angry Deity, Jesus (who Himself is God) in His death was taking our sins on Himself so that He could separate them from us. He did that of His own free will. Death, the irrevocable penalty for sin, was thus carried out in our behalf. This allowed God to remain "just (righteous) and the justifier of him who believes on Jesus." As our Scapegoat He separated all sin from us, making it righteously possible for God to forgive all who will accept Christ as their Sin Bearer.

As Lewis Sperry Chafer wrote almost exactly a hundred years ago in his book, Salvation:"As the righteous Judge, He pronounced the full divine sentence against sin. As the Savior of sinners, He stepped down from His judgment throne and took into His breast the very doom He had in righteousness imposed.... He was the mediator between His own righteous Being and the meritless, helpless sinner. The redemption price has been paid by the very Judge Himself."

Once we become spiritually mature enough to glimpse the rules of the eternal realm, we see that God accomplished on the cross a great deal more than merely establishing some kind of cosmic King's X. He solved His own greatest problem: how to save sinners whom He loved with an undying love and yet still remain true to His own righteous edict regarding sin. By providing a perfect Sin Bearer He eternally separated us from our sin and made it righteously possible to conform us (which He will eventually do) into the very image of our sinless Substitute.

—Steven Ira, as a college undergraduate in English, intended to be an English teacher. He changed his mind, earned an MBA and spent his entire career as a small businessman. Having retired from active business he has returned to his first love, writing.

Throughout most of those business years he regularly studied the Bible, including the works of several well-known theologians: Lewis Sperry Chafer, John Walvoord, Dwight Pentecost, Charles Ryrie, Mark Hitchcock and others. His first three novels in the Daniel Goldman series, "Voices," "Babylonian Harlot" and "The Last Prophet," are based on Tribulation era prophecies, especially those revealed in the Biblical books of Daniel and Revelation. The vision for this series was to write stories about people caught up in the perilous times following the Rapture of the Christian Church. The stories are primarily about those people, yet they carefully follow Bible prophecies about the times themselves.

The Bible offers many specifics about the social and geopolitical circumstances in the period between the Rapture of the Church and the Second Advent of Christ. The series remains faithful to those details. Yet even in this area the Bible allows wide latitude for imagination since it describes only the essences of those circumstances.

In short, Ira's novels seek to show possible, plausible ways in which Bible prophecies of the end times might be literally fulfilled.

Find out more about Steven on his website: https://stevenira.com/ and find his books on his Amazon page: https://www.amazon.com/Steven-Ira/e/B01M7RGMOG.